Every year, the cybersecurity world publishes more vulnerabilities than ever before. The CVE database keeps growing at an impressive pace, and vulnerability scanners dutifully flag thousands of findings in dashboards across the globe.

At the same time, a much smaller list—the Known Exploited Vulnerabilities (KEV) catalog—grows far more slowly.

This raises an important question for security teams and decision-makers:

If CVEs explode in number every year, why doesn’t KEV follow the same curve? And more importantly: which one should organizations really focus on?

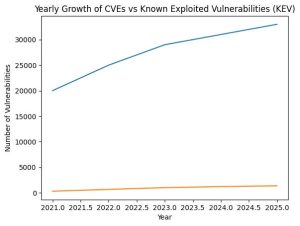

This graph illustrates the diverging growth curves of the CVE database and the Known Exploited Vulnerabilities (KEV) catalog between 2021 and 2025. While CVE volume grows rapidly due to disclosure scale and automation, KEV grows slowly as a curated set of vulnerabilities that are actively exploited in the wild. This difference underlines why risk-based prioritisation matters more than raw vulnerability counts.

CVE growth reflects disclosure, not danger

The Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures (CVE) system was never designed to measure real-world risk. Its purpose is transparency. As soon as a vulnerability is responsibly disclosed and validated, it can receive a CVE identifier—regardless of whether attackers ever show interest in it.

That design choice explains the steep growth curve. In recent years, the number of newly published CVEs has risen from roughly 20,000 in 2021 to over 31,000 in 2024, and 2025 continues that acceleration with more than 33,000 CVEs published. This means the global vulnerability landscape now expands by around ninety new CVEs every single day—most of them disclosed long before anyone knows whether attackers will ever show any interest.

The continued growth in 2025 is largely driven by greater automation in vulnerability discovery, an expanding number of CVE Numbering Authorities (CNAs), and increased visibility into supply-chain and cloud-native software, rather than a sudden surge in genuinely new attack techniques.

The CVE ecosystem, coordinated by the CVE Program (https://nvd.nist.gov/general/cve-process), does an excellent job at cataloguing everything that could be wrong. But that completeness comes at a cost: volume without prioritisation.

For organizations, this often translates into long vulnerability backlogs, endless patch cycles, and dashboards full of “critical” findings that may never be exploited.

KEV grows slowly because attackers are selective

The Known Exploited Vulnerabilities (KEV) catalog exists for a very different reason. Maintained by CISA (https://www.cisa.gov/), KEV only includes vulnerabilities that are actively exploited in the wild and backed by credible evidence.

The growth of the Known Exploited Vulnerabilities catalog tells a very different story. Since its introduction in 2021, KEV has expanded from roughly 300 entries to around 1,200 by the end of 2024. In 2025, the catalog has grown further to approximately 1,350 known exploited vulnerabilities. Compared to the tens of thousands of CVEs published in the same period, KEV continues to represent well under two percent of the total vulnerability landscape—yet it captures a disproportionately large share of real-world attack activity.

This slow growth is not a weakness. It reflects a fundamental truth about cybercrime: attackers do not chase every vulnerability. They focus on what is reliable, scalable, and profitable. Once an exploit works, it tends to be reused—sometimes for years.

In other words, KEV mirrors attacker behaviour, not disclosure volume.

Why equal growth would be a red flag

If KEV were to grow at the same speed as CVE, it would actually indicate a problem. It would mean either that every vulnerability is instantly weaponised (which is not the case), or that KEV had lost its filtering power.

CVE answers the question “What exists?”

KEV answers the much more urgent question “What is being used against organizations right now?”

Understanding that distinction is crucial for modern vulnerability management.

Our view: theoretical vulnerabilities don’t equal real risk

At Guardian360, we believe organizations spend far too much time chasing theoretical risk.

Traditional vulnerability management often treats all CVEs as equal, relying heavily on CVSS scores and raw counts. This approach looks thorough on paper, but in practice it leads to patch fatigue, inefficient use of resources, and a false sense of control.

A high-severity CVE that is never exploited does not pose the same risk as a moderately scored vulnerability that attackers are actively abusing. Yet many tools still prioritise the former over the latter.

That is why we strongly believe organizations should shift their focus from “How many vulnerabilities do we have?” to “Which vulnerabilities actually threaten our business?”

How Guardian360 Lighthouse supports risk-based prioritisation

The Guardian360 Lighthouse platform is built around this exact principle. Instead of overwhelming partners and customers with endless vulnerability lists, Lighthouse is evolving toward a risk-based scanning and prioritisation model.

By combining:

- technical vulnerability data (CVE),

- exploitation intelligence (such as KEV),

- and business context (asset relevance, exposure, and impact),

Lighthouse helps partners focus remediation efforts where they matter most. This aligns naturally with modern frameworks such as ISO 27001 and NIS2, which increasingly emphasise risk-based decision-making over checklist compliance.

The goal is not fewer scans—but smarter outcomes.

Reading the growth curves correctly

The visual difference between CVE and KEV growth curves tells a clear story. One line rises steeply, driven by disclosure and transparency. The other climbs slowly, driven by confirmed abuse in the real world.

That gap is not something to be “solved.” It is something to be used.

Because reducing cyber risk is not about fixing everything that could go wrong—it is about addressing what is going wrong.

Final thought

CVE gives us visibility.

KEV gives us focus.

And risk-based platforms like Guardian360 Lighthouse exist to bridge that gap—so organizations can spend less time reacting to noise, and more time reducing real, measurable risk.